- Home

- Logan, Michael

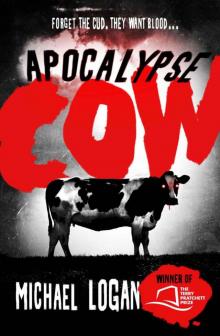

Apocalypse Cow

Apocalypse Cow Read online

About the Book

It began with a cow that just wouldn’t die. It would become an epidemic that transformed Britain’s livestock into sneezing, slavering, flesh-craving four-legged zombies.

And if that wasn’t bad enough, the fate of the nation seems to rest on the shoulders of three unlikely heroes: an abattoir worker whose love life is non-existent thanks to the stench of death that clings to him, a teenage vegan with eczema and a weird crush on his maths teacher, and an inept journalist who wouldn’t recognize a scoop if she tripped over one.

As the nation descends into chaos, can they pool their resources, unlock a cure, and save the world?

Three losers.

Overwhelming odds.

One outcome …

Yup, we’re screwed.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

1. The Beginning of the Rend

2. Of Rice and Zen

3. Tip for Twat

4. In the Belly of the Beast

5. Udder Madness

6. In the Doghouse

7. TV Dinner

8. Armygeddon

9. Buns on the Run

10. Triple-Word Quorn

11. These Little Piggies Went to Market

12. Cold Turkey

13. Letting the Cat Out of the Bag

14. A Midnight Snack

15. Out of the Frying Pan

16. Unhappy Campers

17. Going South

18. Brown and Out

19. Fur Coat, Fancy Knickers

Epilogue: Cruel Britannia

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

In memory of Andrew Logan and Kristian Kramer

Foreword

This novel is not just the joint winner of the inaugural Terry Pratchett Prize, but the joint winner of the inaugural Terry Pratchett Anywhere But Here, Anywhen But Now Prize. Which meant we were after stories set on Earth, but perhaps an Earth that might have been, or might yet be, one that had gone down a different leg of the famous trouser leg of time (see the illustration in almost every book about quantum theory).

We were looking for books set at any time, perhaps today, perhaps, we imagined, a today in a world where two thousand years ago, the crowd shouted for Jesus Christ to be spared, or where in 1962, John F. Kennedy’s game of chicken with the Russians went horribly wrong. We hadn’t considered the possibility of a world in which cows became ruthless, libidinous killers, but it is a tribute to Michael Logan’s imaginative powers that he was able to do so, and serendipitously, to come up with one of the best bovine puns in literary – or should that be cinematic? – history.

The key to creating an alternative world is that it has to be believable – on another variant of Earth, there might be some unusual goings-on, but you still recognize that it is Earth. The physics will be the same as ours: what goes up must come down, ants are ant-sized because if they were any bigger their legs wouldn’t carry them. Apocalypse Cow has stayed true to that – the world it portrays is so slightly removed from our own that it could almost be teetering on the crotch of time, threatening at any moment to change its mind and tip down our own trouser leg. Think about that the next time you tuck into a steak.

Terry Pratchett

March 2012

1

The beginning of the rend

The man in the sharp blue suit stood atop a wooded hill, dangling an expensive pair of leather shoes from one hand, and watched grey smoke belch from the burning abattoir below. A dozen figures in white biohazard outfits ringed the grubby old building, flame-throwers and automatic weapons pointing casually at the ground. He dialled a number on his mobile as the report of cracking glass echoed across the small valley. A great tongue of flame licked from the freshly broken window to caress the underside of the abattoir’s gabled roof.

‘It’s dealt with,’ he said with no preamble.

‘Are you sure?’ a nervous voice asked in response.

The wind changed direction, carrying tendrils of smoke to the watching man’s nostrils. It stank of burning flesh. ‘I’m sure.’

‘If even a single one of those things escaped, we’re finished. And so is this country.’

‘Stop being such a worrywart. They’re all dead, and currently getting nice and crispy in the barbecue.’

‘What about the abattoir workers?’

‘All dead too, save for one lucky individual. We’re bringing him in.’

‘Any idea how the virus got out?’

‘Not yet.’

A heavy sigh flooded the mobile’s tiny speaker. ‘What a balls up. Just make sure you’re gone before the emergency services arrive.’

‘That won’t be a problem,’ the man in the suit replied.

He hung up and looked over the treetops below, to where the long abattoir approach road branched off from the main thoroughfare linking Glasgow with a spray of rural towns. Two fire engines and three ambulances were bunched together, lights flashing furiously, and fruitlessly, at the jackknifed lorry blocking their path.

‘Oh, I’m so good at this,’ he announced to the empty hillside.

He set off down the grassy slope to herd his clean-up team into the waiting Chinook helicopter that would ferry them the few miles back to the facility. Halfway down, his foot sank into something squelchy.

‘Shit,’ he stated, pulling his foot out of an enormous cow pat.

His first concern was for his H. Huntsman suit, which he hadn’t had time to change out of after the call came in from the monitoring team. Fortunately, his foot hadn’t gone in deep enough to taint the hem of the silk trousers, and he’d had the foresight to remove his shoes for the clamber up to the viewpoint. Only the sock was ruined. He could live with that.

Disaster averted, he considered the significance of the cow pat. Pools of dark blood slicked the surface of the generous dollop of dung, which the coated sole of his foot told him was still warm. He raised his head, and scanned the tree-line. The smoke was growing thicker and darker as the flames consumed flesh, plastic, wood and metal. It drifted between him and the wood, obscuring his view. He thought he saw a bulky body moving among the tree trunks, but when it melted away he dismissed it as a clump of smoke. Then he heard it: a long and shuddering moo, emanating from deep within the trees. The moo came again thirty seconds later, quieter this time. It was moving away, towards the rolling fields where thousands of dairy cows grazed in blissful ignorance, and the suburbs beyond.

‘Oops,’ he said, and hopped down the hill as fast as his unsullied foot could carry him.

2

Of rice and Zen

Geldof Peters had never encountered a hemp plant. If he did he would kick, punch and stamp on it until it lay in a ruined pulp beneath his shoes, which were made of hemp. The ignominy of being beaten to death with a product made from the corpses of its brethren would escape the plant, but he would revel in it.

While an innocuous plant may seem undeserving of such vitriol, Geldof had good reason for his vendetta. For as long as he could remember, he had been dressed in hemp. His shirts, trousers and underwear were all made from the fibre, to which he was horrendously allergic. Every part of his body itched furiously and his neck and wrists, chafed by collar and cuffs, were ringed with a scabby rash.

He laid the blame at the door of his mother, who was upstairs pottering around as he sat on the sofa reading the latest Iain M. Banks sci-fi epic and trying not to claw himself raw. He had tried to convince her that the rash was hemp-induced. She refused to believe him. Instead of going to a doctor like a sensible parent, she had dragged him to her spiritual advisor – a wizened old man

who had swapped the soaring mountains of Nepal for Cumbernauld, where the only thing soaring into the sky was the ugly 1960s concrete block of a shopping centre. The mystic had diagnosed a severe case of spiritual malaise and advised him to seek his true path in life. Geldof had been hoping for some kind of cream.

Non-hemp solutions were unacceptable to Fanny Peters, environmental campaigner and humongous pain in the arse. Leather and suede, by-products of the meat industry, were forbidden in the vegan household. Nylon was out because it was part of ‘humankind’s relentless march away from Mother Nature’ and denim was deemed too mainstream. Geldof was allowed Fairtrade cotton, but since Fanny had a deal on hemp clothing from one of her friends, he only owned a few cotton items – which had anyway become contaminated by hemp fibre and were almost as bad.

It was all right for her. She wasn’t called ‘Scabby Peters’ at school. She didn’t suffer the embarrassment of scratching her neck in class and having a large piece of skin fall off, only for Malcolm Alexander to spear it on a pencil and parade it around the squealing girls. She wasn’t the one who couldn’t get a partner in Scottish country dancing class and had to stumble around with Mrs Flaxton, the geography teacher-cum-dancing expert, who reeked of mothballs and gin.

While the rash was the main target of abuse at school, it wasn’t the only feature to provoke teasing. Geldof wore glasses, had been born with the curse of ginger hair, and was incredibly scrawny due to his habit of tipping half of his unpalatable vegan meals down the toilet when his mother wasn’t looking. These invitations to bullying negated the fact that the rest of his face was rather well put together: his eyes were a shade of blue that would be called ‘icy’ or ‘piercing’ if anybody actually bothered to look beyond the obvious, his nose was on the cute side of pug, and he sported dimples that had prompted unrestrained, and unwelcome, cheek-tugging by passing middle-aged ladies when he was younger.

Once you added in the fact he was English in a country of rabid English-haters, had been saddled with a ridiculous name and was in the habit of carrying around far more books on maths than strictly necessary, it was clear why Geldof was miserable, even by pubescent boy standards.

Life had its small consolations, though, and one of them was baiting Fanny at every opportunity. As his mother’s calves appeared at the top of the stairs, Geldof fell to his knees, clasped his hands and began to pray loudly with his eyes squeezed shut.

Fanny sighed when she stopped in front of her son. ‘Praying again. You know Christianity is responsible for the worst atrocities to disgrace this planet.’

Geldof broke off to say in a neutral tone, ‘I’m just trying to experience all religions to see which one fits. You told me I should stay open-minded about my spirituality.’

In the ensuing silence, he suppressed a grin. There was nothing more satisfying than throwing Fanny’s own words back at her, particularly when it justified his fake Christianity. He had even considered joining the priesthood, but thought committing himself to a lifetime of Mass, alcoholism and playing Snap! with nuns just to annoy his mother might be overkill. Plus the Catholic Church was fervently anti-masturbation, as his English teacher Sister Maria was fond of ramming home when she was supposed to be introducing them to literature. This policy clashed with his frantic rate of fiddling, which was only gathering pace as he approached his sixteenth birthday.

Only a few things could dampen Geldof’s libido. When he opened his eyes, one of the chief culprits was hovering six feet away: the jungle of black hair sprouting from between his mother’s legs, even more unruly than her dreadlocks. Two long hairs protruded from the thicket like the antennae of a Madagascar hissing cockroach. Even though her penchant for nakedness meant he had seen it all before, it was still an unnerving sight. He hopped back up onto the sofa.

‘You’re right, I’m sorry,’ Fanny replied eventually. ‘Please just pray quietly. I’m about to meditate.’

‘I’ll be quiet if you and Dad stop running around naked,’ Geldof muttered. ‘It’s embarrassing.’

‘I only want you to be comfortable with your body,’ Fanny said reasonably. ‘If you stop wearing clothes at home too, you won’t feel embarrassed.’

‘In the changing rooms last week, the PE teacher said I looked like a skeleton draped in tissue paper,’ he snapped. ‘Why would I want to put that on show?’

Maybe because you wouldn’t be as itchy, a little voice in his head told him. He ignored it. He would rather flake away to nothing than be naked in the same space as his parents. That was wrong in every way imaginable.

‘Your PE teacher is misguided,’ Fanny replied. ‘Your body is just as beautiful as anybody else’s.’

She reached for Geldof’s hand. He ignored the conciliatory gesture and pointedly reassumed the prayer position. Her drooping smile prompted a small pang of regret, which he quickly suppressed. She wheeled away, and within seconds of her disappearing upstairs, whale song kicked in, setting the Chinese lampshades dotted around the room vibrating. Geldof gritted his teeth. Fanny’s yodelling mantra began. If he had had anything else to grit it would have been firmly gritted.

He crossed to the mantelpiece and began stacking the statuettes of Buddha, Krishna and other gods into a pyramid. Like most of the knick-knacks around the house, the figurines came from the shop of new-age tat Fanny ran in Glasgow’s West End. Had she located it anywhere else, the business would have closed in a week. But the proximity to Glasgow University meant hordes of drink- and drug-addled students frequented the shop to blow their loans on dragon-shaped incense burners, ethnic jewellery and books on lucid dreaming.

When Geldof was satisfied the tableau would be sufficiently annoying, he stood at the window and ran a finger around the inside of his collar, trying to ease the nip. His father, James, was in the back garden, impervious to the misty spring rain drifting through the air to speckle the windowpanes. He was watching a squirrel shimmy across a rope towards a pillar with a transparent plastic tunnel fixed to the top. James virtually lived in the back garden, either in the shed, devising new obstacle courses for the squirrels and taking notes on their performance, or tending the vegetable garden that provided the ingredients for many of the family’s meals – all accompanied by continuous spliff-smoking.

James looked just like the animals he studied. His grey ponytail kinked up and down like a squirrel’s tail and his face looked as if somebody had grabbed the end of his nose and pulled his features forward a few inches. Even his eyebrows were grey and bushy, like squirrel fur. Only his slow movements, and the fact he was six foot and clad in cords, sandals and a parka, differentiated him from the twitching rodent scurrying through the tube towards a pile of mixed nuts. Geldof was convinced his father’s obsession with setting up assault courses derived from his army days, before he was reborn as a peace activist. Not that he had ever discussed the army with his father. James’s mind was always somewhere else – probably in the void, given the amount of Gold Seal he smoked each day.

Geldof opened the patio door and stepped into the garden to escape the racket for a few minutes. The smell coming over the tall wooden fence Fanny had erected to keep the surrounding middle classes at bay captivated him instantly. He stood on a stone tiger and peeked over. Through the pulled-back flowery curtains of the next house, he spied Mary Alexander – his neighbour, maths teacher and love of his life – contemplating two steaming plates of mince and potatoes.

He closed his eyes and sucked in air through his nose. The glorious, forbidden meat smelled as divine as Mary looked. Her little paunch was pressed against the table top and her dark-framed glasses sat halfway down her nose as she twirled a lock of wavy hair, staring at the plates. Geldof could almost hear her massive brain whirring. She was probably calculating the forces of attraction between each globule of mince or pondering the mathematical complexities of the vortices of steam that rose from the food. She scooped up a lump of mince with her index finger, sucked it and ran her tongue the length of the digit to clean off the gravy

. The blood in Geldof’s legs rushed off, urgently required elsewhere. He fell off the tiger.

Once he had recovered, Geldof stood up and headed for the gate. His mother had settled into her meditation, while James hadn’t even noticed him collapsing to the ground a few metres away. He didn’t intend to eat anything, as Fanny had a nose like a drug-squad dog. If she detected meat on his breath, his computer privileges, and thus access to the recreational maths websites and chat forums he frequented, would be withdrawn. That would be a punishment too horrible even to consider. He simply wanted to bathe in the rich aroma of the mince. The Alexanders didn’t mind him coming over, and the twins would be at football practice or lurking in the park smoking, so he wouldn’t get any grief from his chief tormentors.

Geldof crossed into his neighbours’ property and tapped on the door. A few seconds later, David Alexander threw it open.

‘Hello, son,’ he said. ‘The wails of the banshee driven you out, have they?’

With a non-committal shrug, he followed David into the living room just as Mary came through with the food. Geldof eyed the meals with the despairing look of a de-clawed, toothless cat tracking a fat mouse.

‘Want some?’ David asked, balancing a plate on his large stomach.

Geldof looked away guiltily.

‘Mum will be making dinner soon.’

‘What you having?’

‘Rice cakes in a tomato and red pepper sauce.’

‘Sounds fucking disgusting,’ David said, and spooned a large pile of mince into his mouth. Some of the meat clung to his beard, while more plopped onto his Led Zeppelin T-shirt, surrounding Robert Plant’s head like a beefy halo.

‘You sure?’ he asked between mouthfuls.

‘Stop torturing him,’ Mary said. ‘You know he doesn’t eat meat.’

Apocalypse Cow

Apocalypse Cow